Article by: Adam Manning

Edited by: Harry T. Jones and J. D. Dixon

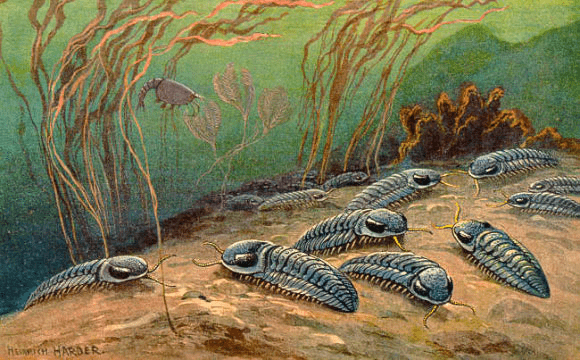

Trilobites (Class: Trilobita) are some of the most well-known prehistoric creatures ever to be discovered. They were extremely diverse, with over 20,000 species, abundant, and widespread, found all over the world. They were also an extremely long-lived group of animals, first evolving in the Cambrian and finally going extinct in the Great Dying at the end of the Permian. So what made trilobites so successful?

Trilobites are among the first-ever arthropods, which include animals like insects and arachnids, and were exclusively marine. Profallotaspis jakutensis, found in Siberia, are among the oldest trilobites discovered so far, dating back to the Early Cambrian. Trilobites were extremely successful in the Cambrian. This is because they had many new evolutionary traits, including a hardened outer skeleton, which protected them from the new predators lurking in the ancient seas, and allowed them to move of their own accord to find food. They also had eyes, another innovation which allowed them to see food and threats coming and act suitably. Whilst they certainly weren’t the first or only creatures in the Cambrian with such features, they still proved to be incredibly useful, allowing trilobites to flourish and diversify throughout the Paleozoic Era.

B) Isotelus rex, the world’s largest trilobite. Taken from Rudkin, et al. (2003).

Trilobites came in a myriad of different sizes, shapes and lifestyles. The biggest trilobite discovered so far is called Isotelus rex, dating back to the Ordovician. It was 70 cm long, longer than the diameter of a dinner plate. On the other side, the smallest trilobite discovered so far is Acanthopleurella stipulae, which was only 1.5 mm in length. Furthermore, many trilobites in and after the Ordovician had elaborate spines and bulbs, such as Boedaspis ensifer. Whilst they may have had some defensive abilities, it has been suggested it is more likely that their primary function was as secondary sexual features, like the features developed on insects such as rhinoceros beetles. One of the cutest trilobites was Opipeuterella, a tiny Ordovician trilobite with huge eyes and a narrow, streamlined body. It was a trilobite adapted for swimming through open water, swimming on its back as it hunted for zooplankton.

Trilobites were one of the most successful groups of animals ever to exist on our planet, continually evolving and diversifying into thousands of different forms, with a wide variety of morphologies, modes of life and diets. They even managed to survive two of the world’s worst mass extinctions, the End-Ordovician and End-Devonian extinction events, before finally getting wiped out at the end of the Permian. So perhaps these bugs have something to teach us about adapting and surviving the world’s biggest challenges.

Image References

[1] Trilobites by Heinrich Harder (1916).

[2] A) Acanthopleurella stipulae, the world’s smallest trilobite. Taken from Dorey et al. (1980).

B) Isotelus rex, the world’s largest trilobite. Taken from Rudkin, et al. (2003).

[3] Boedaspis ensifer, an Ordovician trilobite equipped with protruding spines. Click Here.

[4] Opipeuterella in dorsal view and in its swimming position. Click Here.

Information References and Further Sources

[1] Bushuev, E., Goryaeva, I., and Pereladov, V. (2014). ‘New discoveries of the oldest trilobites Profallotaspis and Nevadella in the northeastern Siberian Platform, Russia’, Bulletin of Geosciences, 89 (2), pp. 347-364. Accessed 23rd September 2020. Click Here.

[2] Fortey, R. A., and Owens, R. M. (1999). ‘Feeding Habits in Trilobites’, Palaeontology, 42 (3), pp. 429 – 465. Accessed 23rd September 2020. Click Here.

[3] Fortey, R. A., and Rushton, A. W. A. (1980). ‘Acanthopleurella Groom 1902: origin and life-habits of a miniature trilobite’, Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Geology, 33 (2), pp. 79-89. Accessed 23rd September 2020. Click Here.

[4] Gon III, S. (Unknown) ‘A Guide to the Orders of Trilobites’. Accessed 15th September 2020. Click Here.

[5] Knell, R. J., and Fortey, R. A., (2005). ‘Trilobite spines and beetle horns: sexual selection in the Palaeozoic?’, Biology Letters, 1, pp. 196-199. Accessed 24th September 2020. Click Here.

[6] Perrier, V., Williams, M., and Siveter, D. J. (2015). ‘The fossil record and palaeoenvironmental significance of marine arthropod zooplankton’, Earth-Science Reviews, 146, pp. 146-162. Accessed 24th September 2020. Click Here.

[7] Rudkin, D., Young, G. A., Elias, R., and Dobrzanski, E. P. (2003). ‘The world’s biggest trilobite – Isotelus rex new species from the Upper Ordovician of northern Manitoba, Canada’, Journal of Paleontology, 77 (1), pp. 99-112. Accessed 24th September 2020. Click Here.