Interview by: J. D. Dixon

Edited by: Lauren Malin and Harry T. Jones

This week, our virtual interview was with Emma Hanson, a third year PhD student studying micropalaeontology. We got to find out all about her current studies, how scientists are connecting with young people globally, and how palaeontology can lead to worldwide friendships.

Hi Emma, thank you so much for taking part in the series. Firstly, could you tell us a little about yourself?

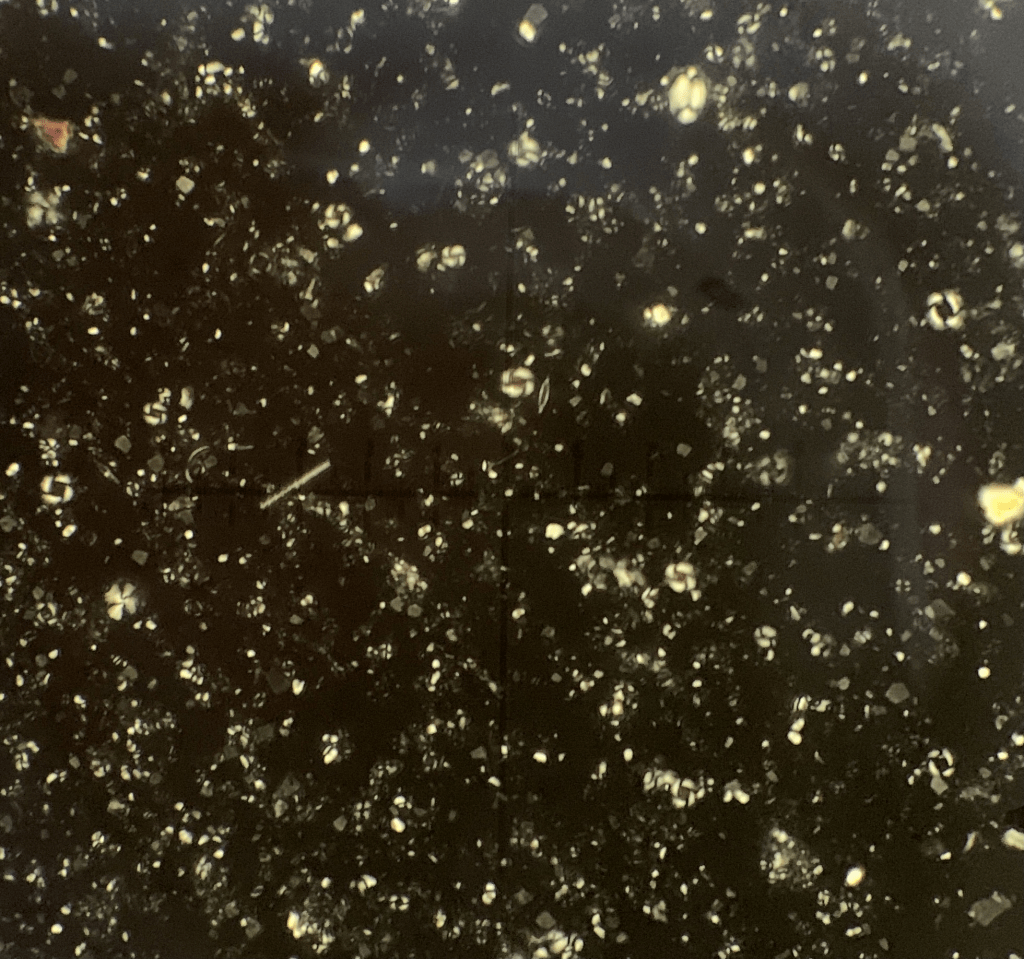

“Hello, I’m Emma (she/her), a third year PhD student studying in micropalaeontology, particularly coccolithophores which are super tiny single-celled organisms that live in the ocean and have been around since the mid-late Triassic. I am a first-generation university and PhD student originally from Blackpool, a small seaside town in the North-West of England. I have a dog called Hugo and, although I am probably biased, I am pretty certain he is the best dog in the world. I really enjoy baking and reading, and will spend most of my weekends doing this!”

When did you decide you wanted to be a palaeontologist/geologist?

“When I was completing my Geography A-Level, I realised the parts that I liked the most were about volcanoes and earthquakes. When I started looking at which degree to study at university, I realised these were major parts of Geology so went with that! It was only during my undergraduate degree when I had a couple of lectures on palaeontology did I realise how fascinating it was. Although we only had one or two lectures on microfossils, I was hooked by them and went on to do the Micropalaeontology MSc at Birmingham, which I started in 2016. During the MSc I became really interested in the application of microfossils in palaeoclimatology, which is the study of past climates.”

What is it like studying for a PhD, and how does it compare to other studies you’ve undertaken?

“Studying for a PhD is very different to completing a BSc or MSc. You are a lot more in charge of your own work and time, and there is a lot more freedom to broaden your interests – I really enjoy outreach work so have become a lot more involved in this, whether that’s through video chats with schools or attending festivals and workshops. There’s also massive scope to create collaborations all over the world and work with people you’d have never usually gotten the chance to. One of my favourite parts of the PhD is the opportunity to travel. I’ve been to multiple conferences in the US and had the chance to go to Qingdao, China, and present my work last year, an opportunity I never would have gotten. On these trips you always meet a lot of new people, leading to new friendships all over the world. It’s cool as well having the chance to complete research. Often you are asking questions that haven’t been answered or looking at things that haven’t been done yet, and it’s always exciting when you figure out something you’ve been trying to find the answer for.”

You’re aiming to set up an automated analysis system for biostratigraphy data collection. It sounds very complicated, so could you explain what this is and what your ultimate goal with this would be?

“When looking down the microscope at nannofossils, you can often see upwards of 400 individual nannofossils, of which you need to count and record each individual and the species that you see. This takes a long time to do and is often an intensive activity, taking a lot of concentration, meaning you might not be able to do a lot of samples at once. One of the aims of my PhD is to automate this data collection and analysis, so you’d be able to put a sample underneath the microscope and leave the computer to do it for you. This would take much less time than a person doing it, would hopefully be more consistent and would mean a lot more samples being able to be analysed, leading to a bigger data set. Unfortunately COVID-19 has put a bit of a stopper on this, but hopefully I’ll be able to get into the lab soon and get it up and running!”

What do you hope to advance to after your PhD?

“Honestly, I’m not 100% sure. I’m really enjoying doing research and answering scientific questions, so it would be cool to carry on with this. However, my mind changes daily at the minute, and I think that’s okay too!”

What would you say was your proudest moment with regards to your field?

“Part of my PhD is to look at the geochemistry of coccolithophores. Usually, because they’re so small (about 0.003 – 0.03 millimetres!), it would be a really laborious process trying to separate them to complete isotopic analysis on them and you’d only end up with a few samples. So, we came up with a new method that was much quicker and allowed many more samples to be analysed. Seeing the results of our first round of isotopic analysis and realising that the new method worked was really exciting, and I was proud and happy that all the work that had gone into preparing the samples had been successful!”

What would you say has been your best fieldwork experience?

“Although fieldwork is often an important part of palaeontology, my samples come from the bottom of the ocean off the North-West coast of Australia and were collected via a scientific cruise, so I don’t have any fieldwork with my PhD. I think it’s important to remember that not all geologists/palaeontologists do fieldwork, and a large part of studying and learning is done indoors, whether that’s looking at a model on a computer, looking down a microscope at nannofossils or studying hand specimens of fossils and writing notes.

However, I am part of a training programme with my PhD and we do fieldtrips on that. We went up to the North East coast of England, where there are some amazing Jurassic outcrops similar to the ones on the South coast. Whilst wandering round Robin Hood’s Bay, I came across two ichthyosaur vertebrae with a bit of rib still attached, which was by far my best fossil find and the best fossil find on the trip. Also, any field trip down to the Jurassic Coast in Dorset will always be one of my favourites because the scenery is beautiful!”

What was it like attending the American Geophysical Union (AGU) 2019 meeting? How did you find the travel, events, and the experience as a whole?

“The AGU 2019 meeting took place in San Francisco, USA, and it was the second largest conference that I went to in the US. These conferences are massive (there were about 40,000 people at this one) and take place in convention centres with people coming from all over the world. It’s so hard to describe how big they are, but when it takes 15 minutes to walk from one talk to another, hopefully that puts a bit of perspective on it! Overall, experiences like this are amazing – you present your science to a lot of people, meaning you get new perspectives on things you might not have thought before. These can then lead to career-long collaborations and introductions to new projects and research. They are often very tiring days – a full day of talks and then going out to socialise in the evening, but they’re definitely worth it. The travel was also fun. I’d decided to tag on a trip before the conference, so I spent a week and a half going around California, seeing Yosemite National Park and Monterey. It was the perfect thing before the busy week that was the conference. However, I realise I am very privileged to be able to attend events like this, and I do believe more work needs to be put in to make these events more inclusive and accessible.”

How did you get involved with Skype A Scientist, and what was it like talking to young people interested in pursuing science?

“Like most things, I came across the Skype A Scientist programme via twitter. The programme is international and aims to link scientists from any field with school children of any age from all over the world. I know colleagues who have done it with 16 year olds in London, to 10 year olds in New York. I was linked up with 6 year olds in Utah, who were very excited to talk to a palaeontologist. A lot of children don’t have access to a lot of different scientists, so it’s always fun to answer questions from them. Most of the time the kids know the basics of who they’ll be talking to, so all they knew about me was that I was a palaeontologist. Although they came armed with a load of dinosaur questions, they learnt new things about microfossils which they had never heard of before, and that’s always fun. Although I always have to be prepared with some dinosaur facts…”

Following on, do you have any helpful tips or wise words for people who want to become palaeontologists?

“Do what you find fun and interesting! Palaeontology offers insight into how an organism lived during a different time, and the answers you can get from this can help to shape modern ideas about some animals. A palaeontologist uses a lot of different sciences, so it’s good to study a broad range before specialising in palaeontology.”

And for our last question, what is one weird palaeo fact that you think people should know?

“Coccoliths are so small that on an average thumbnail you could fit between 10-15,000 individuals on it!”

I’d like to finish with a big thank you to Emma for taking the time to talk to us this week and provide insight into the world of microfossils. For more information about Emma or to find out how to contact her, check out her Twitter and Instagram!