Article by: Adam Manning

Edited by: Harry T. Jones, Jack Wood, and J. D. Dixon

Name: Nigersaurus taqueti

Age: Early Cretaceous (Aptian – Albian)

Diet: Herbivore

Size: 10-15m in length approx.

Weight: 4 tonnes approx.

Location: Niger, North Africa

Sauropods are some of the most iconic dinosaurs of all time, probably due to the sheer size of most of the group, which is almost beyond our comprehension. One of the most interesting, and bizarre, examples from this clade of dinosaurs is the rebbachisaurid Nigersaurus taqueti.

Nigersaurus was a ten-to-fifteen-metre long sauropod, first found in the Elrhaz Formation in the African country of Niger, hence its name. It was discovered in 1997 by a team from the University of Chicago, USA, who found the remains of hatchlings as well as several adult specimens. The species was first described in 1999. It lived around 110 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous.

The most striking feature of Nigersaurus is its shovel-like mouth, earning it the nickname “The Mesozoic Lawnmower”. Its mouth was broad, with a flat straight edge that extended to each side of the skull, attached to a relatively short skull (for a diplodocid). However, some of the bones of the skull roof were extremely slender and delicate, meaning that Nigersaurus likely had a very weak bite, even for a herbivore.

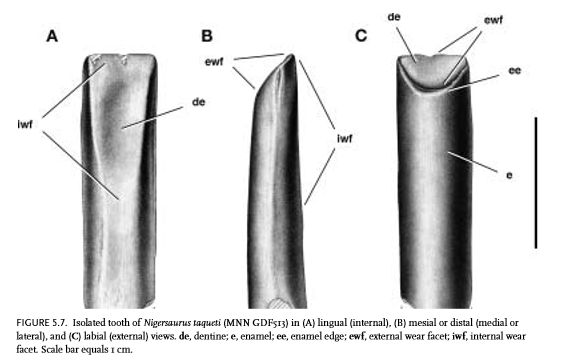

Nigersaurus had hundreds of extremely small, thin teeth, positioned to form tooth batteries. Tooth batteries are defined as a tooth composite made up of self-supporting teeth that erupt and wear in unison. The teeth of Nigersaurus were uniform throughout the mouth, except the teeth on the lower jaw were slightly smaller. Nigersaurus also had up to eight replacement teeth behind each one and has been estimated to replace each tooth once every 14 days. This is almost twice as fast as most other sauropodomorphs and is the highest known replacement rate of any dinosaur.

Putting these modifications together meant that Nigersaurus was well adapted for its particular niche as a low browser. Its short skull allowed it to get close to the ground to crop plants with its rake-like batteries of teeth and immediately swallow them, instead of prolonged chewing like in ornithischians. Having such a high rate of tooth replacement meant that they were always optimised to be the most efficient at shearing. Therefore, it didn’t need a strong bite to browse on soft, low-lying plants, and could use its long neck to reach plants in a huge area without needing to take a step. Unfortunately, such specialisation to this niche likely meant that when the environment changed, the food sources Nigersaurus relied upon disappeared, causing its extinction.

Upon the discovery of Nigersaurus, scientists now know that tooth batteries had evolved at least three times independently in dinosaurs, twice in two groups of ornithischians and in rebbachisaurids. However, due to the difference in the function of the teeth and the time difference between the appearance of the adaption in each group means that this is unlikely to be the product of convergent evolution due to a single environmental cue, such as the evolution of flowering plants.

Image References

[1] Nigersaurus taqueti, in the flesh and without. Art by Tyler Keillor/Photo by Mike Hettwer, Project Exploration, ©2007 National Geographic.

[2] An isolated tooth of Nigersaurus taken from Sereno and Wilson (2005).

Information References and Further Sources

[1] D’Emic, M. D., Whitlock, J. A., Smith, K. M., Fisher, D. C., and Wilson, J. A. (2013). ‘Evolution of High Tooth Replacement Rates in Sauropod Dinosaurs’, PLOS ONE, 8 (7): e69235. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069235. Accessed 8th July 2019. Click Here.

[2] Dixon, D. (2007). The world encyclopedia of dinosaurs & prehistoric creatures. London, England: Lorenz Books. pp. 262.

[3] Sereno, P. C., Wilson, J. A. (2005). ‘Structure and Evolution of a Sauropod Tooth Battery’, in Curry Rogers, K. A., and Wilson, J. A. (eds.), The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. University of California Press, Berkeley. pp.157-177. Accessed 8th July 2019. Click Here.

[4] Sereno, P. C., Wilson, J. A., Witmer, L. M., Whitlock, J. A., Maga, A., Ide, O., and Rowe, T. A. (2007). ‘Structural Extremes in a Cretaceous Dinosaur’, PLOS ONE, 2 (11): e1230. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001230. Accessed 8th July 2019. Click Here.

[5] Upchurch, P., Barrett, P. M., and Dodson, P. (2004). ‘Sauropoda’, in Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H (2nd ed.) The Dinosauria. University of California Press. pp. 263.

[6] Updike, J. (2007). ‘Extreme Dinosaurs’, National Geographic. Dec 2007. pp. 50-51.